|

Vaughan Family Timestream® Maps |

| Home Biography People Places Multimedia: Making It Work On the Water Writings/Presentations |

Marine Insurance and the Small Craft Surveyor

W. Taylor Vaughan, III

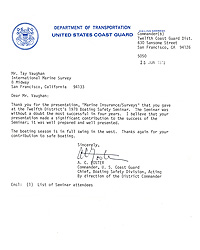

A talk delivered before the Fourth

Annual Boating Safety Seminar sponsored

by the 12th Coast Guard District at the

Eldorado Hotel, Reno, Nevada. 10 May, 1978.

There is some irony of time and place in discussing Insurance and Surveying here in Reno, since the subject concerns the measurement of odds and risk in the marine environment. What better place than this city to discuss odds? I trust most of you have in the last twenty-four hours tested yourselves in the theater of risk - and that some of you have survived while some, now with a mixture of frustration. and thinly-veiled equanimity ( I'm afraid I share this category with many of you) have not fared as well.

The purpose of my talk is to outline the mechanics of risk measurement of small craft and recreational marine exposure and to provide some understanding of its bearing on Boating Safety. For most of us in this room . it is our directive to reduce the risk of accident, injury, and unsafe practice.

Let me begin by shotgunning some statistics at you as they will help define the target of our interest. These data are complied from material supplied by the Boating Industry Association, the National Association of Engine and Boat Manufacturers, the American Water Ski Association. the Coast Guard, the Department of Commerce and individuals and other groups. They are 1977 figures.

52,575.000 Americans participated in recreational boating, using the waterways more than once or twice during 1977.

13,000,000 people went waterskiing

35,500,000 fishermen wetted their lines

4,200,000 people went skin and scuba diving

10,515,000 pleasure craft of all types and sizes plied U.S. waters in 1977.

5,920,000,000 was spent at the retail level for new and used equipment, services, insurance, fuel, mooring and launching fees, repairs and boat club memberships.

With all this activity in 1976, the Coast Guard listed only 8,954 boats invoLved in reported accidents, some 1,264 reported fatalities, and some 1,838 non-fat8l injuries. 1977 figures indicate a fatality rate for this sport of some 9.6 thousandths of a percent. Not too bad in my book, but still 24 thousandths of a percent too much.

What's it all about? It's about a Calling to the world of water. It's about a magical mixture of smells and dampness, of serious romance, of adventure and control of destiny, of quiet Wisconsin muskie lakes and downhill ocean passages in 20-foot following seas. It's even about high-speed power boats. waterski parties on the levee, and good times with good people. Even before Cleopatra's famous barge floated down the Nile, ships and boats were used as pleasure craft. Never before, however, have boats and small craft been so readily accessible to so many people as in the latter half of the 20th century. In California alone there were some 535,883 state-registered watercraft in 1976 with 7,671,213 registered nationwide for that same year.

With this perspective, now, let's talk about Marine Insurance, as it is through this vehicle that risk is transfered, using dollars as a medium. While gambling has been claimed to be the oldest known sport (I emphasize sport, as there are professions which claim to be older), Marine insurance is recognized as the oldest form of indemnity of which there is any record. In many ways they are similar. As long ago as 900 B.C. the merchant adventurers of Rhodes were insuring their ventures with "bottomry bonds."

Marine insurance has been historically inseparable from the carriage of merchandise and cargoes. In 1310, the Lombards and the Hanseatic League, then rulers of western commerce, established a "Chamber of Assurance" at Bruges where records indicate that, on a single tide, as many as 150 vessels would arrive at the outer harbor. Since the Middle Ages the method of indemnity hAs changed from "Bottomry" to the acceptance of risk by underwriters. In the early days, shipowners and merchants obtained loans from bankers and money lenders, offering their vessels or goods as security, and repaid these "bottomry bonds II upon a successful arrival. If the vessel or goods were lost at sea or the venture failed, the loan was forfeit, and the lender lost all.

Contemporary insurance methods are essentially the reverse of this system and generally free underwriters from this direct and intimate involvement in the transactions of commercial ventures. The shipowner or merchant now purchases from an underwriter an agreement that, in case of loss or damage through specified causes or perils, the underwriter will recompense the assured an agreed amount usually representing the fair value of his vessel and/or cargo.

In 1779 Lloyds, still to this day an organization of individual underwriters who often share large risks, developed a lengthy standardized policy form which was approved by the British Parliament. During the centuries of its use, Admiralty Courts have interpreted, defined, and closed any ambiguities, and most underwriters have been hesitant to develop other, more current, tenns and expressions fearing that the long process of judicial review would only begin anew.

The principles of ocean marine insurance are applied to commercial operations today as they were in Edward Lloyd's time, and great tankers and cargo vessels are covered by policies which are dark with fine print. Insurance for yachts and watercraft without commercial enterprise, however, is gradually evolving a vocabulary of its own, and forms and procedures are becoming streamlined.

Each underwriter has his own formulas for the calculation of premiums, particularly for yacht and small craft insurance, All begin with a figure derived from past records. Some begin with a base rate and apply surcharges; others begin with a higher rate and make deductions. Rates will certainly be lower if the vessel is new and sound and remains in home waters under an experienced owner. Though "collision" is the most common claim, "fire" causes the greatest financial loss for insurance companies.

The most significant factors in determining the recent rapid rise in the cost of yacht policies are repair and replacement costs. In 1965, underwriters paid about six dollars per hour for repair yard labor. In 1978, these rates have risen as high as twenty-two dollars or more per hour. The price of hardware and construction have, over the same period, gone up as much as 300% for some items. You have to remember, marine insurance is indemnity, or "making good "New is replaced for old when repairs are effected. And, like other types of insurance, Admiralty Courts have been making high awards to claimants. Surprisingly, however. over the last ten years, despite the increases in insurance premiums, when expressed as a value of the vessel they have actually gone down.

Unless required by a bank or other lender as a condition of a loan, the decision to insure a pleasure boat remains that of its owner. Because trade warranties define navigational boundaries (usually within a set radius of home port), travel beyond these limits requires additional endorsements and premiums. Some transoceanic yachtsmen who find the costs prohibitive elect not to purchase insurance. Many uninsured enjoy succesful adventures: others become the grist of sad tales passed from boat to boat.

The sea itself is a gamble. The elements of nature are at best uncertain, and at worst disastrous. And those mariners who transfer risks through the purchase of insurance must be cautioned never to fall prey to false security. In a disaster, papers and fine print will do little to avert or allay trouble. Later, perhaps, when perils have been avoided or met and overcome (or when the sea has triumphed), the gamblers can count their wins and their losses as they have since history began.

The insurance world consists of brokers and underwriters. In a sense, brokers can be considered as personal representatives of the insurance purchaser: they go out into the insurance marketplace and negotiate the actual transfer of risk. Brokers may deal with one, or more often, many underwriters, and for their services they receive a commission or fee which is incorporated into the premium payment. A good marine insurance broker will work closely with the boat owner to gather all the appropriate or required information regarding the vessel, its condition, its operation and the experience of its crew. The broker then "shops" the marketplace to obtain the best coverage at the best price. A yacht insurance application usually includes the following:

1. A description of the vessel and its condition

2. An outline of the owner's prior experience including past losses and formal boating education such as at Power Squadron or Coast Guard Auxiliary courses.

3. A description of waters to be navigated.

4. Specific coverages requested, including hull and machinery, protection and indemnity (liability), medical payments, personal effects, trailers, etc. Usually, a deductible is required and may range from $100 to several thousand dollars or more depending upon circumstance.

5. Where the yacht will be moored and whether it is safe and protected.

One major underwriter states that "as a normal part of our underwriting procedure, a routine inquiry may be made which will include information concerning character, general reputation, personal characteristics, and mode of living."

Rates themselves vary, depending upon the broker's ability to shop the marketplace; they depend also, of course, upon the risk exposures involved. Rate structures and formulas are closely-guarded industry secrets. The insurance world is competitive, and underwriters (particularly successful underwriters) will not reveal their trade secrets. But neither will the white-haired probabilities professor who visits the gaming tables twice a year and who quietly but successfully manipulates odds and risks.

A primary working tool of the underwriter is the marine surveyor. On vessels over 26 feet in length a survey of age, condition, seaworthiness, equipment, and fair market value, is usually required.

The surveyor's opinions provide the data necessary for the underwriter to establish his premium or, in some cases, to refuse to accept the risk. Underwriters are under no obligation to "gamble." There are no "assigned risks" in marine insurance. The more information entered into the premium formula, the better can be measured the risks.

I would like to talk for a while generally about the profession of marine surveying. Then I will tell you a few stories where the names have been changed to protect the guilty as well as the innocent.....

There is no definition of the term "marine surveyor" that adequately covers all those persons who practice under that name. Commander John McCurdy, U,S, Coast Guard (Retired) listed three categories of surveyors in an article in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings in December, 1975:

First is the classification surveyor. There are nine classification societies in the world. ranging from the American Bureau of Shipping to Lloyds Register to Bureau Veritas and to Det Norske Veritas. Each of these societies has its own rules and regulations for the construction and repair of ships, but they generally read the same. Classification rules are applied by individual surveyors who possess years of experience over the entire range of shipyard crafts and skills. Classification surveyors are mainly selected from merchant marine engineering officers and shipyard men. These surveyors enjoy the respect and deference of the maritime community at large in recognition of experience and the burden of decisions which involve great costs to all parties concerned: shipowners, charterers, consigners, and underwriters. Decisions of the surveyor can be appealed, but rarely are - he IS the society on the scene. And rarely does a day pass that the classification surveyor does not commit an act of judgement involving a ship that, on some future day, he may be summoned before an admiralty court to testify on. These are judgements that may also cost lives.

Second is the association surveyor. These are the surveyors called upon to provide expert knowledge and assistance to minimize loss or damage. The surveyors advise on what should be done with damaged cargo, they establish causes of loss or damage, and they work closely with both owners and underwriters. They also negotiate repair costs, arrange for salvage and towing costs, and they represent the interests of the party which has retained them.

Thirdly, and including the world of recreational and small craft boating, is the independant surveyor. These are individuals who feel they are qualified to offer their services to interested shipowners, charterers, merchants, or underwriters. Also in this category re associations of surveyors of diverse backgrounds offering services over the entire spectrum of hull, cargo, and machinery survey, including professional naval architects and marine engineers. Among the business the independant surveyor finds himself engaged in includes ship appraisal, investigation of casualties, testifying as an expert witness, and acting on behalf of clients who have need for expert opinion.

As far as I know, in 1978 there exist practically no government regulations or requirements in the marine surveying field. With few exceptions, no states require licensure or professional documentation. A lone surveyor might go into business with as little capital investment as a business card.

In the yacht and pleasure boat industry this has created some problems. What we find at work in the field of small craft surveying is a natural selection process similar to Darwin's concept of "survival of the fittest." While any individual might sell his opinion, that opinion needs a marketplace and a buyer. It takes a while for natural selection to weed out those surveyors who enter the business with inadequate qualifications. The final test of qualification is too often determined by survival, and, in the meantime, some purchasers of this not-too-expert opinion suffer.

To survive, a small craft surveyor must be recognized as competent by not only a prospective buyer or yacht broker, but also by the underwriters and lending institutions which ultimately utilize his survey report. Banks and insurance companies maintain lists of "approved" surveyors. Approval by these institutions can be a formal procedure of qualification and experience review. In an area as large as San Francisco Bay, for example, there may be as many as a dozen or more qualified small-craft surveyors who will be listed as "approved" by the major banks and marine underwriting offices.

In 1960, the National Association of Marine Surveyors was formed "to encourage cooperation and to provide communication between the members. assist in the exchange of information concerning the latest approved and recommended practices for new materials and their application to the marine field.

In 1977. N.A.M.S. had approximately 300 members. However, due to still-existing "political" fractures within the surveying profession, not all qualified surveyors have wished to join this organization.

The best way to find a competent marine surveyor is to ask the underwriters and the banks. They have had experience with surveyors' reports and can give good advice. A yacht broker or dealer is not always the best person to turn to, as his prime interest may be "making the sale." And it is a good idea to be sure your surveyor's report will be accepted before you engage him.

In the small craft field the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) has emerged as the organization most closely related to the large vessel classification societies and works very closely with the Coast Guard. Its manual, "Safety Standards for Small Craft," is a significant and, to those of us in the field, extremely helpful compilation of recommended practices in boat construction and operating safety. Most recently the ABYC has developed both an electrical system compliance guideline and a fuel system compliance guideline under a contract to the Coast Guard. Both manuals address the specific provisions of the Federal Regulations in CFR 33 and are of great use to boat builders and others in the field .

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) also publishes guidelines for motor craft fire protection (publication number 302) which is presently being revised and brought up to date. "302" has for years been the traditional standard reference for underwriters of small craft, but as the ABYC has grown and matured, NFPA has fallen behind the latter in both comprehensiveness and scope.

The Marine Division of Underwriter's Laboratories ' (an offshoot of the old Yacht Safety Bureau) also publishes specific standards for small craft equipment as well as conducts tests on materials.

I have brought with me copies of these publications for you to look at during the break. These are essential reference materials for anyone in the small craft safety business and they, are, of course, primary tools of the surveyor's trade.

When Commander Foster first asked me to address this Boating Safety Seminar and to talk about insurance and surveying, I thought immediately of the many interesting stories I could tell you... The tales of experience and events in the life of a small craft surveyor out in the field. And I cannot leave you without some idea about a surveyor's involvements and about the public which both he and you have to deal with.

A navy submarine officer in San Diego outlined to me several years ago, an experience which puts some of the boating public in perspective. He was a guest aboard a Coast Guard 80-footer operating in the channel between Los Angeles and Catalina Island when heavy fog set in. About eight miles offshore and underway at four knots, the bow watch called the bridge to warn of a small motorboat ahead. They stopped the engines while a Boston Whaler came alongside with one person aboard. The fellow called up to the bridge: "Which way is San Pedro?" and the bridge replied to "standby while we get you a bearing." A couple of minutes later the bridge called down through the fog something like "7 1/2 miles, steer 92° magnetic." Then the fellow started waving his hands and yelling, "No, no, Point! I don't have a compass!"

The public are not all like this, and I have dealt with many a vessel owner who showed not only common sense and prudence but also true concern for his and his passengers' safety. But it is the boat operators without compasses who make the news and who, worse, endanger not only themselves but others as well.

Some time ago I was asked to examine a sailing yacht which had been run down by a freighter off the Golden Gate. The aft quarter had been stove in and some considerable damage had been done to the fiberglass hull. The owner explained in great detail and with some anger the events that led to the accident. He planned to sue everyone he could. But you know, as I listened to him talk I was remembering the thousands of sea miles I have sailed in small craft in shipping lanes, and I realized that there was an essential part missing from his account, and it related directly to his aggressive personality. He lacked prudence. Regardless of the fine points of the right-of-way laws, would you step out in front of a semi on a four-lane highway to exercise your legal right as a pedestrian? Other accounts from witnesses indicate he tacked across the freighter's bows to the continuing tune of repetitive blasts from the larger vessel. Anyway, this case is, I am sure, still being litigated.

The boating public is sorely lacking in consistency. Some are well informed and conscientious, others are dangerous in their lack of knowledge end safety practices. While inroads are being made in terms of vessel construction and equipment regulations to improve safety, there reamins the difficult question of operator qualification. In 1978, there are no laws governing the qualifications of pleasure boat operators. The only laws seem to apply to reckless or negligent operation and "driving under the influence..." This seminaar is not the proper forum for a licensing discussion, and I am aware of many pros and cons. But it remains a problem which is directly linked to safety and is on the minds of many of us.

Let me end my presentation with an account of great drama and survival. About a year ago I was asked by an underwriter to represent their interest in a suit evolving out of a tragic mid-ocean accident. On delivery to the U.S. from Japan a 60-foot racing sloop encountered a series of nasty gales north of 40 deg. latitude. Seas were reported running twenty to thirty feet with an occasional maverick wave coming across the normal train. Winds were gusting over sixty knots, the ambient water temperature was 39 deg. Fahrenheit. At 12:50 in the middle of the night, with two persons on watch in a miserable spray-swept cockpit, the yacht tumbled off a freak wave, rolling 360 deg. and dismasting. One man in the cockpit waS thrown overboard; his partner was crushed by a full 55 gallon drum of spare diesel fuel. Below, the vessel was a shambles and utterly dark.

Within four minutes the man overboard had been plucked from the water still on his lifeline harness. Shortly thereafter his partner (with a compound fracture of her leg) was below in a bUnk. At daybreak, a jury-rigged radio antenna was working and a mayday message had been sent to the Coast Guard in Kodiak. The broken mast, which was beating against the hull, was cut away. 12 hours later a Hercules 130 was overhead, guided by an an Emergency Locating Transmitter. After six passes to measure drift using smoke bombs, the Hercules dropped an 800-foot line to windward, with two 20-man rafts at either end and survival canisters in the middle. It floated neatly to leeward and was retrieved by the crew of the damaged boat. Then, some 40 hours after the accident, a Danish freighter came on station, and two hours later the Coast Guard vessel Mellon was at the scene and put a doctor on board. The damaged vessel was towed to Kodiak, surveyed and repaired, and is today again fully functional. No lives were lost.

Two points can be distilled from this accident which hold true for all pleasure craft, and I will leave you with them:

Firstly, safety is the proper construction and outfit of a boat with attention to detail and to emergency equipment.

And secondly: Safety is the experience, foresight, and prudence of a boat's operating crew.

Combining these both in an ocean racer or waterskiing an inland lake, that twenty thousandths of a percent fatality rate can be significantly reduced.

Ladies and gentlemen, it has been a pleasure to be here with you, and thank you for listening.