|

Vaughan Family Timestream® Maps |

| Home Biography People Places Multimedia: Making It Work On the Water Writings/Presentations |

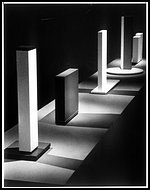

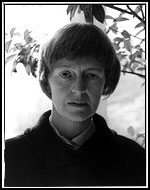

Anne Truitt

Interview with Anne Truitt

Conducted by Anne Louise Bayly

At the Artist's home in Washington, DC

April - August 2002

Preface

The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Anne Truitt on April 16, 17, 25 and August 8, 2002. The interview was conducted at Anne Truitt's home in Washington, DC by Anne Louise Bayly for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Interview

MS. BAYLY: It is April 16, 2002, and this is Anne Bayly interviewing Anne Truitt for the Archives of American Art, at the artist’s home in Washington, D.C.

Why don’t we talk a little bit about your childhood in Easton, Maryland. I’ve read in your books that your first experience with seeing art or seeing a painting would have been when you saw a Renoir at a friend’s house, was it?

MS. TRUITT : No. That was my first experience of seeing great art. My house was full of art, just full of it. My forebears were Boston -- were New Englanders who owned clipper ships that went to the Orient, to China, and so I grew up in a house full of Chinese things, full of Chinese Canton china and beautiful tapestries, which are now -- now that I’m 81, those tapestries are coming back into my work. Very interesting to me. Very interesting to me. One hung upstairs in the upstairs hall and the other one hung in the dining room, and they were both very beautiful, old -- very old, ancient -- Chinese tapestries. And my mother had a beautiful Chinese Mandarin coat, which came down to me.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wow.

MS. TRUITT: Fascinating tapestries because, of course, details are subsumed into a whole and yet no detail is lost.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And the whole effect is one. The colors of those beautiful tapestries are so well keyed that nothing is lost. And my grandfather had been ambassador to The Hague and he bought art in Europe, so the house was full of French furniture and the house was full of sculpture. There was a marble pedestal in the front hall with a bust of Caesar Augustus on it. That was, I suppose, since the beginning, that. And then on an inlaid French sort of chest with a marble top in the living room was a fascinating bust, I thought, of Marie Antoinette which was part enamel, part gilt and part marble.

MS. BAYLY: Wow.

MS. TRUITT: Almost Rococo, but more restrained.

MS. BAYLY: Did you feel free to explore these objects in your house? Did your parents keep the children in a nursery or somewhere else, or did you feel that you had free rein to go and touch the tapestries?

MS. TRUITT: Oh, I could do whatever I pleased. My parents never interfered with me. The only thing they did was make sure I wore ground-gripper shoes and ate three square meals a day and had a nap every day after lunch. And I was required to do those things. And then I was required to let them know where I was.

MS. BAYLY: Right. Certainly.

MS. TRUITT: Other than that, I don’t think I had any restraints put on me. And any questions I asked were answered as fast as they could be asked. I was taught at home until the fifth grade by a governess. My parents set up a little “dame’s school” overlooking our garden. And my two younger sisters, 18 months younger than I -- twins -- and I -- that’s three students, and then my oldest friend, Helena Johnston, was one of the students. She’s about two years older than I. And then there were two little girls who were my contemporaries.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: Or our contemporaries, my sisters’ and mine. Helena died about five years ago, my lifelong friend since I was a baby.

MS. BAYLY: I’m so sorry.

MS. TRUITT: And one of the other little girls died, Peggy Chapman. But Kitty Chapman I’m back in touch with because I had an exhibition in Easton about five years ago or something --

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wonderful.

MS. TRUITT: -- and I looked her up again. I sort of tracked her down. Very interesting. Those little girls were both adopted. One came from Denmark and one from I don’t know where. They were very different little girls. So there were six little girls and we were taught in a room overlooking the garden by this wonderful woman named Ms. Francis, whom I talk about, I think, in “Turn.”

MS. BAYLY: Yes, and you went back and you saw her much later.

MS. TRUITT: Much later, when I was in my sixties -- or was it seventies? And yes, I went over to see her in Denton, Maryland. I was so glad to see her and she was so glad to see me. I think probably both equally glad. I think she must have been a little bit curious, although she had not, I think, really liked me when I was a child.

MS. BAYLY: Really?

MS. TRUITT: I think perhaps I was really not all that agreeable a little girl, in the sense that -- in the book I said I asked her if I was interesting and she said no. Ms. Francis was always so honest. But then when we met again, when she was in her nineties and I was in my sixties, we liked -- we had so much in common, you know.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So I’m awfully glad I did that. And my temperament is such that I tend to -- I go back and re-collect -- not only recollect, but re-collect experience that interests me or that I feel is unfinished.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I do it all the time. I do it with books. I re-read books. I read War and Peace and Anna Karenina each four times, and I might re-read them again before I die. I re-read in order to double check what I think.

MS. BAYLY: Is this something you’ve always done?

MS. TRUITT: Yes.

MS. BAYLY: Even when you were a child you would do this?

MS. TRUITT: Yes. My mother used to read to us every night on that little sofa you’re sitting on.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, this one right here?

MS. TRUITT: Yes.

MS. BAYLY: And you were saying [The] Lady of Shalott was one of your --

MS. TRUITT: Well, that we used to read up in her bedroom from that chaise longue over there, which was in the bedroom. And right next to it, just as it is here in my living room, there was a fireplace and a fire. And we used to sit up there and she had tea every afternoon. We’d read and have tea. My mother was wonderful. She read to me in her beautiful voice. She went to Radcliffe. Very interesting person. And her mother went to Smith. I come from sort of a line of bluestockings.

MS. BAYLY: Yes. Well, besides reading to you, did your mother let you just explore on your own -- I read that you, of course, got a bike one day and were able to ride around Easton and go exploring on your own.

MS. TRUITT: My father gave me the bike.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: It was like the Mes Eglise way and the Guermantes way, to some extent, in Proust, although God knows I’m – you know, that sort of may be drawing -- it’s not drawing a long bow, it’s just using Proust as a paradigm. My parents came -- my mother came from Boston, my father from St Louis. They met in Cuba in the First World War. And they went to Cuba because my grandmother, my mother’s mother, had very bad arthritis and her habit was to go to Aix les Bains in France every year for her arthritis, but she couldn’t go during the war, so they went down to Bermuda, and my father -- to Cuba – I beg your pardon -- and my father was there.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: And so they met. And then they met again in France in the first -- during that war, where my mother went as a Red Cross nurse and my father was in the Army.

MS. BAYLY: Oh. So they sort of left one another in Cuba, and then --

MS. TRUITT: I think they stayed in touch, I gather.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: So then they met again in France and they were married on May 8, 1919. Would that be correct? Yes, it would be correct. It is correct. It was in New York.

MS. BAYLY: And from there they moved to Easton, where they --

MS. TRUITT: Yes. They moved to Easton. And I wish I’d asked more questions. I always asked a lot of questions, but the questions weren’t the right questions, necessarily. [Laughs.] I think they moved there because my father’s sister married a man who lived there.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: They lived out at Avonville, which was a house out in the country, and we always lived in the town.

But I began to tell you about the difference between my father and mother.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: Not only was I in a situation in which the Guermantes way was represented by my parents, who came -- they were foreigners in this very provincial -- in the very best sense of the word, in a French sense or an English sense -- sort of “county,” that kind of thing. They were foreigners. What the Japanese call gaijin, outlanders. Gaijin is Japanese for foreigner.

MS. BAYLY: How do you spell that?

MS. TRUITT: G-a-i-j-i-n.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: So that gave them a kind of distinction -- I don’t mean distinction in the sense of distinguished -- distinction in the sense of being distinct in the community. And the reason why I was taken in on the eastern shore of Maryland had nothing to do with them, although it did have to do with them because they were also to some extent distinguished. They stood out. It was the fact that Helena Johnston and I were such good friends. Her family had been there for I don’t know how many generations. Sort of native-born Eastern Shore people, Washington and Eastern Shore.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: So that gave me a place on the Eastern Shore. What I’m really leading up to is the fact of why this is so charged for me, the whole Eastern Shore. It was the first thing I opened up my eyes on. I think it’s very important what you open your eyes on first. There’s a kind of decision that you have to take as you go through your life: whether you’re going to stay in your body, so to speak, whether you’re going to look at it realistically or actualistically and whether you’re going to settle and address yourself to the situation. [Laughs.] I think the first environment on which you open your eyes tends to tincture or tint or color the way in which you view the world from then on.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: The exterior world as opposed to the psychological world.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So the first things I opened my eyes on were in the Eastern Shore. And they’re still there in my work. I’m still, you know, never -- it’s just ingrained in me. And because of the freedom that my parents gave me -- my parents were very intelligent; they let me alone. You know, that’s a huge boon.

MS. BAYLY: I think you said, as your mother said, to raise children like cabbages?

MS. TRUITT: Yes.

MS. BAYLY: And give them lots of space and let them be to grow.

MS. TRUITT: The minute she said it, I saw exactly. I saw myself as a cabbage on a --

MS. BAYLY: [Laughs.]

MS. TRUITT: [Laughs.] -- on a well-cultivated field with the sun and the rain and plenty of space around me so my leaves could go out as far as I wanted. That’s exactly what she did. And I think many parents pore over their children. You know, they want them to be something. I was born when my father was 42 and my mother was 32, and it was a big pleasure to them when I was born, and then my sisters followed 18 months later. And I think I, in particular, was a very great pleasure to my parents, and particularly my father, who really thought -- he just adored me; there’s no point of fooling around with it. And I think that gave me the thing that perhaps little girls get from their father, a feeling of real affirmation, a kind of inner confidence that I notice that very few people have.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: It doesn’t occur to me to question my decisions. My deep decisions, the ones that I make out of myself. And I’ve always looked on the inside to make decisions, and I think part of it is that sort of natural confidence.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Plus the ground-gripper shoes, the orange juice, the brown bread. The fact that I was expected to be able to go out into the world on my own and stay there for the morning as soon as I got old enough.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And the bicycle my father gave me, which gave me wheels under me, and independence. Plus the fact that my mother read all the time to us, and my father read to us, too.

MS. BAYLY: So really, though you were in a smaller -- you know, Easton, and you were just a small person -- your world was actually quite vast, I guess, if you were reading so much and you were able to go around on your bike wherever you wanted.

MS. TRUITT: Completely fascinating. I just loved my childhood.

MS. BAYLY: That’s wonderful.

MS. TRUITT: Then when I was about 13, the axe fell on me. But you’re quite old at 13.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I just adored it. I thought it was so interesting. Of course, for the eastern shore of Maryland -- if you’re a child, you’re low down to the ground.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: And the landscape is low. It lies down under the sky, sort of like Holland. Van Ruisdael. You know, that lowlands -- the low horizon?

MS. BAYLY: Yes. Yes.

MS. TRUITT: Yes. If you think about it. Have you been over there?

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: It’s a Dutch landscape. Or Rembrandt, The Three Trees etching. The water is here on the horizon, and then just a few little incidents above it, and then the sky.

MS. BAYLY: The sky.

MS. TRUITT: So the horizon is set very low. And if you’re a child, you have the enormous advantage of being low down. And then you have the advantage of the fact that when you are low down, your little naked feet are in the ooze. [Laughs.] And because of the fact that Helena Johnston was two years older than I was, I had even more freedom because I had the freedom of being with an older child.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And she was a very prudent person, which I am not. So we used to play in the ooze and note everything that goes on where the water and the land interchange.

MS. BAYLY: And you just kind of explored everything.

MS. TRUITT: We just looked at everything. And Helena had a bicycle too. Hers was blue and mine was red. But mostly I went on my bicycle alone. She had a house in the country, and that was a big boon to me because then I had all the swimming and all the things having to do with the river and all those pleasures. The pleasures of childhood.

MS. BAYLY: And you said, Anne, I guess it was -- was it Prospect or Turn? -- that her mother was great fun and was always --

MS. TRUITT: Oh, her mother was wonderful. I called her “Ju-uey” because I couldn’t say “Julia.” I was really too young. See, we were lifelong friends. I miss her every day. Ju-uey was perfectly wonderful. She was -- she’s what they call “intellectual,” a word I really almost never use, but she was. Her mind was very far ranging and she was very interested in entertaining new ideas, and she loved poetry. Well, my mother did too, but my mother was not so -- my mother was better educated. She’d been to Radcliffe and her context was very different, you see.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Her context was very much wider than Ju-uey’s, but she didn’t have that kind of -- she didn’t have the temperament of somebody who jumps at things. So Ju-uey was just a lot of fun. I mean, if she liked Yeats, she loved Yeats. So she just would read Yeats and we’d just sit and listen. Or she always had a lot of papers around her, so you could pick up her papers. That’s how I found out about Freud. Pick up her papers and read what she was reading. She was a clipper.

MS. BAYLY: And she would encourage this in you?

MS. TRUITT: I never paid any attention to what she thought. The papers were all over her bed. She had a great big bedroom and she had two beds in it, and the other bed was always full of papers. I don’t think the older people had that much effect on me, other than to just set me free. Other than -- I mean, you’ve asked a couple of questions now about what I was allowed to do.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I never had the feeling that I was being allowed.

MS. BAYLY: To do anything.

MS. TRUITT: I just had the feeling that I belonged, and I made choices of what I was going to do and not do, within reason.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And if I had questions, I would go and ask my mother.

MS. BAYLY: And she would usually be forthcoming?

MS. TRUITT: Oh, completely. Completely. She had a lot of faith in me. She was right.

MS. BAYLY: So once you --

MS. TRUITT: She was right because I was level-headed.

MS. BAYLY: And so she could trust you to --

MS. TRUITT: Yes, she could trust me. She brought me up to be trustworthy, and my father did too. And then they trusted me. And so what they got was this little girl who knew what she was doing. Sturdy-legged, strong little girl. Independent. Also, my family’s house was not universally cheerful. So my father drank and my mother was sort of really not awfully well all the time. So it was a little bit gloomy. But you see, from my point of view, I had my bicycle, and then the weekends I almost always spent out in the country with Helena. So I had a great deal of compensation. And one of my first decisions was to turn out of my family.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I don’t think families are that -- you know, you don’t have to stay with the egg forever.

MS. BAYLY: No.

MS. TRUITT: And I stayed a very short time.

MS. BAYLY: Now, you went away to high school?

MS. TRUITT: Excuse me?

MS. BAYLY: Did you go away to high school?

MS. TRUITT: No, I didn’t. I was taught until the fifth grade in the – under that situation, and then the Depression hit. Well, from my point of view and the point of view of -- my mother was about to send me to the National Cathedral School or something like that. And I think because of money, because they lived on inherited money, and the money was cut by the Depression, she decided she’d send -- also, Ms. Francis married. She got married.

MS. BAYLY: Oh. So she, of course, needed to leave and --

MS. TRUITT: Yes, so the little school came to an end and I was put, thank God, into public school.

MS. BAYLY: In Easton?

MS. TRUITT: Quel shock! It only happened to one other person I’ve ever known, Jamison Parker. He and I used to discuss it.

MS. BAYLY: It must have been quite a shock.

MS. TRUITT: It was a terrific shock. And we both hit it simultaneously, both in the fifth grade. It was wonderful! It was just wonderful! It’s like nursing. It was the way nursing was for me when I hit Red Cross nursing.

[Telephone rings.] You needn’t worry about the telephone.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: If I hadn’t gone to public school, I wouldn’t know anything.

MS. BAYLY: Really. Was it the experience of being with many different students, or was it that the curriculum was so different, or -- ?

MS. TRUITT: Well, the curriculum was different. That’s a good point. The curriculum, of course, was far more objective. It was the first time in my life that I was required to meet objective standards, because Ms. Francis didn’t like arithmetic.

MS. BAYLY: Ah.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. So when I hit the fifth grade, I knew that five times five was 25 because something about it stuck in my head. I knew three times five was 15 and seven times seven was 49, and of course I knew the second table and I knew three times three was nine. But actually, there were huge blanks. There just were blanks. And I could figure it out because I’d been taught how to figure it out by adding on my fingers, you see. But it was a tough sort of transition because, first place, the standards were objective; second place, there were about 30 children in the classroom, or 25 to 30. Now, I had never seen that number of children before. I’d never seen any boys.

MS. BAYLY: Really?

MS. TRUITT: Except, you know, just at a distance.

MS. BAYLY: That must have been mind-altering. You know, just so opening for you.

MS. TRUITT: Oh, it was wonderful. And I was so different from the others, and yet so much alike. I had little pigtails and I wore these cotton dresses that were made for me, with little collars and cuffs. And there were big boys at the back of the room -- I can see them now, two of them -- who were really quite big. I think they had been too badly taught to go from grade to grade, and they couldn’t pass them so they were just kept in this classroom at the back. And they giggled and laughed and threw spitballs and stuff. Why, I was fascinated!

And then I had a friend named Johnny, who was a little boy in my class, the first -- the second friend who was a boy. I did know one boy, little Billy, Billy Miles. Billy Miles and I were friends when we were about two years old. We used to sit on the step in the sun and talk, I guess. I don’t know what -- I don’t remember --

MS. BAYLY: And he was a neighbor?

MS. TRUITT: He was a neighbor.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: And then Johnny was my first friend through whom I learned what it was like to be desperate. And he and I walked home from school one day. I don’t know what he thought. We sat down on the curb in front of my house, in the dirt, you know, with our feet in the dirt, and he had on a sweater that had big holes in it. He was very poor and it was the Depression. The Depression was far more depressing than anybody seems willing to talk about now. They talk about depressions nowadays. They don’t know what they’re talking about.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Depressions is when -- depression -- a depression is when people have nothing to eat. I mean, it’s a serious matter. And the pain of it and the suffering is perfectly terrible. I remember seeing a man rooting in a garbage pail near my house. And my father did a great deal of work with the Red Cross and the Children’s Aid Society, trying to help. It was truly terrible.

Well, little -- this boy, who was a very nice boy, he and Billy Miles were the prototype of the friendships with men that I’ve had all my life. I have very good friends who just happen to have been men. So we sat on the – scuffled our feet in the dirt, and then the next day he disappeared. He never reappeared. I remember going in and walking upstairs to my mother’s bedroom, where she was working at the desk which I now have in my bedroom, and I said, “There’s a little boy who has holes in his sweater and I like him a lot. He’s such a nice person,” et cetera. I don’t know how I said it. And Mother said, “Well, we’ll see what we can do,” meaning that she would keep an eye on him and help him. But he disappeared.

MS. BAYLY: Where do you think he --

MS. TRUITT: Oh, I think he went back to the farm.

MS. BAYLY: To work?

MS. TRUITT: He probably was just given a couple of days in school, you know, or -- I think it was in the spring; it was warm enough to sit outside. So maybe when warm weather came, he went back to work on the farm. But he was an intelligent, strong-minded boy with character. I’ve never forgotten him. I haven’t the faintest idea what happened to him. I can’t go back and pick him up. If I could, I would. I don’t even know his last name. If I knew his last name, I’d ask Tom Bartlett, who lives on the eastern shore of Maryland and still -- and knows everything. He’s like me; he collects everything and keeps it in his memory.

MS. BAYLY: So it must be hard for you to have some of these things that you can’t re-collect and --

MS. TRUITT: No, but that’s the way life is. And also, whatever was, whatever experience you have had cannot be taken away from you.

MS. BAYLY: Right. That’s, of course, very true.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah.

MS. BAYLY: How long were you in the public school in Easton?

MS. TRUITT: I think it was two years, maybe three. I went into the fifth grade. How does it go in schools? By the eighth grade I was in -- by the ninth grade -- nine, 10, 11, 12 -- I was in St. Anne’s. So the eighth grade I went -- it was eight, seven -- you can see my math – six, five. So four years. But I moved from the grammar school to the junior high.

MS. BAYLY: Okay. And were your sisters enrolled in the same --

MS. TRUITT: My sisters were two grades below me. They went into the third grade.

MS. BAYLY: And they went all the way through, as you did?

MS. TRUITT: They went through. And then they went to -- we by that time moved to Virginia and they were in public school in Virginia near my aunt’s farm outside Charlottesville, and I went to St Anne’s in Charlottesville for a year. And then we moved to North Carolina, and then I went to St. Genevieve of the Pines in Asheville. And I graduated from there in 1937.

MS. BAYLY: D you have any sort of artistic or arts classes there at all?

MS. TRUITT: No, none.

MS. BAYLY: Or art history?

MS. TRUITT: Absolutely none. The only thing I remember when I was a child that had to do with drawing or -- oh, yes, two things. One of them is I went to Sunday School and we had these horrible crayons and horrible books with pictures of Jesus and little children and stuff, with big, thick black lines. Do they still have those?

MS. BAYLY: Oh, yes, they have them.

MS. TRUITT: They do? And crayons. We were supposed to fill in. But I knew it was completely useless.

MS. BAYLY: Yeah, it is.

MS. TRUITT: I was obedient, vaguely. I found it profitable to be obedient when I was a child because if you’re obedient, people leave you -- they trust you. Reasonably obedient.

MS. BAYLY: And they give you more freedom.

MS. TRUITT: You don’t have to be slavish, but you do have to do what’s right, get up in the morning and get dressed and go to school and do well in school. I loved school. I love school; I’ve always loved it. I’ve always adored it, ever since I hit the public school.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But Ms. Francis, I really did more or less what I pleased. Ms. Francis, the only thing she ever did in the way of art was make a flour map of the Andes.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, yes, I read that. It was sort of a relief map. It was wonderful.

MS. TRUITT: And we painted it green and white. It was lovely.

MS. BAYLY: Did you feel particularly attracted to the activity of making and creating something like that? I know you said later when you were at your aunt’s farm in Charlottesville you saw them making soap or creating or making things on this farm.

MS. TRUITT: “Creating” is a word I just never use, you know. I think God creates. We just make things.

MS. BAYLY: Making.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. But I know how you’re using it. I’m not correcting the word or anything.

I never really thought about it much. I mean, when you breathe, or when you move around, everything seems to me of a piece. But I’ve always liked making things, yes. I like the fact that something comes out of nothing.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But I never gave it much thought.

MS. BAYLY: So you didn’t feel, though, when you were --

MS. TRUITT: In fact, I never gave it any thought.

MS. BAYLY: Really, until you were much older and --

MS. TRUITT: Well, not until 1948.

MS. BAYLY: Right. So when you were a child, then, and you were experiencing the landscape -- the Eastern Shore and the layout of the town and how --

MS. TRUITT: And the light.

MS. BAYLY: -- and the light -- you were just sort of experiencing them as they were, but did you not feel an urge to sort of capture them and --

MS. TRUITT: I never thought of myself at all, except I thought how interesting everything was. No, I felt no inclination whatsoever.

MS. BAYLY: So it was just thoroughly --

MS. TRUITT: I just was busy absorbing, like a sponge. In fact, I’m still the same way. I never make sketches. I never draw unless I’m making a work on paper. I never just fiddle. I don’t need to. I’m a sort of one-shot person. I’m terribly serious, I’m afraid. The problem is I’m really very serious, and if I do something, it’s really serious.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And there was no need for me to. In my house there were a lot of pictures, French pictures, and there were beautiful old ship pictures. There’s my mother.

MS. BAYLY: Oh! Oh, that’s beautiful.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah, she is beautiful, actually. There she was painted when she was 19. There were beautiful ship prints because of the clipper ships in the Boston stuff, history. The house was full of beautiful things, really. And the sort of still lifes you see in books, sort of 19th/18th century with dead hares and things -- though I don’t remember any dead hares, but that kind of thing. Big floral pictures.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah, dark. Dark. And I would not call them beautiful. I would call them sort of first-rate third rate, or first-rate second rate, something like that. They were --

MS. BAYLY: [Laughs.] That’s a good description.

MS. TRUITT: -- practitioners. They were artists who were practitioners. The first work of art I ever saw was that little Renoir on my way out the door at the Arensbergs. And I think that’s Conrad Arensberg. I think those are the Arensbergs who collected the Arensberg Collection, oddly enough.

MS. BAYLY: Wow.

MS. TRUITT: Funny how life is, isn’t it?

MS. BAYLY: It is. And so that was what really struck you, though.

MS. TRUITT: Was that painting. I would never have held up the line otherwise. I mean, I was very polite. But that’s a wholly different order of things. I saw that art was possible to make something of an entirely different order.

MS. BAYLY: An --

MS. TRUITT: Entirely different order. Art bears no relation to life at all. Very little.

MS. BAYLY: All right.

Well, after you moved to North Carolina and you completed high school, you went on to Bryn Mawr, where you studied psychology.

MS. TRUITT: Yes. I think we should dwell a tiny little bit on Asheville because that’s where I --

MS. BAYLY: Oh, absolutely.

MS. TRUITT: No, we don’t need dwell very long. There, instead of the landscape being flat and horizontal and without incident, there I encountered mountains. Fat, bulky, filled, powerful, shouldering shapes. And I was very interested in that. Closing you in. Closing the landscape, closing in the horizon and looming. Things looming over you. I was very interested that the -- I mean, valleys and clefts and Courbet-like landscapes. It was just a totally different place. And different colors. And different people, with whom I felt really virtually nothing in common. I mean, I was really isolated there.

MS. BAYLY: Did you feel sort of isolated --

MS. TRUITT: Exiled.

MS. BAYLY: -- from the landscape?

MS. TRUITT: No, not a bit. I never feel --

MS. BAYLY: The landscape --

MS. TRUITT: I never felt exiled from what’s around me.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I shouldn’t say that, because I did in Japan.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: But Japan really is different. But we’ll get to that, I suppose.

But Asheville, I learned two things. One was the mountains. The second was discipline in family life. My parents were really never well after the age of 13. They just weren’t. I learned the discipline of family life. I learned to bear up and endure. That’s a very good thing to learn. And I learned to live in a very alien environment, not only the people around me -- whom I didn’t love. I mean, there was nobody I loved except my family, whereas in Easton, there were plenty of people I loved.

And then I learned the discipline of more Latin. I’d already had two years of Latin. Then I took three more years of Latin and learned the structure better. I studied Cicero and Virgil. I learned the structure of the language better because the structure of my sculpture comes, to some extent, from the structure of Latin.

MS. BAYLY: Yes. I studied Latin for a long time and --

MS. TRUITT: You did?

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: Good.

MS. BAYLY: So I was actually very interested in reading everything that -- you know, you kept sort of referring back to the poets and the Greeks, but I didn’t know necessarily your work was based on the structure of Latin --

MS. TRUITT: The Latin --

MS. BAYLY: -- [off mike].

MS. TRUITT: -- sentence, you could -- well, then you know what I’m talking about.

MS. BAYLY: Yes, absolutely.

MS. TRUITT: The Latin sentence is a very plain sentence. They’re clear-cut. The nouns are nouns. They stand up straight. The verbs carry the action, and sometimes they stop the action, and sometimes they carry it. And sometimes they don’t come till the end of the paragraph, like Caesar’s praeponic [sp] sentences. I think the structure is just completely fascinating.

MS. BAYLY: It is. It’s so simple, yet says so many --

MS. TRUITT: It’s blocks. They’re in rectangular, in square blocks. So that the nouns and the verbs and adjectives, everything has a place and it’s orderly. And it’s expressive, but the expression is not necessarily in the words themselves, but in their juxtaposition, their connection, to make sense.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: It was a revelation to me. I adored Latin from the beginning. I began to study it in Easton. I had --

MS. BAYLY: In the public school?

MS. TRUITT: Yes, in the public school. I was taught by a wonderful woman. I think her name was Ms. Lord. She was very tall and very thin and she wore a lot of bright clothes. She’s the sort of person that Sherwood Anderson would have latched on to as being typical, sort of spinster teacher. And she later married. She married a man whom I also had my eye on when I was a child, who was very fat. Not too tall, and very fat, and I always was interested in that. And they married.

MS. BAYLY: And then did you --

MS. TRUITT: He courted her. He courted her and he married her, and I saw the whole thing from my bicycle. And I cared about her because she was teaching me this absolutely wonderful stuff and I was learning as fast as I could learn. And my mother was a Latin scholar, really, much more than I, and she studied it all the way through college. So we could talk about it. My mother and I talked a great deal about objective things -- Jane Eyre, poetry, Latin, French. She spoke beautiful French, and I studied French too. I got extremely good French teaching in Asheville because the nuns were French. I’m not a Catholic.

MS. BAYLY: Right. But it was a convent school that you were --

MS. TRUITT: I learned about the structure from the convent, too. It was the first time that I saw a structured religion, because the Episcopal Church -- you know, if you say you’re sorry and you’re an Episcopal person, Episcopalian, you’re all right.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I mean, there isn’t any such thing as something landing on you or anything. Dante is very alien to them.

MS. BAYLY: Wow. I’m sure that being in a monastery or in a convent is extremely structured and --

MS. TRUITT: Extremely what?

MS. BAYLY: Structured. Did you like the structure of it or were you drawn to it, or did you feel that there was like sort of a lack of freedom?

MS. TRUITT: I disliked it. I thought it had no air.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: It had no air. I realized then that I must never get -- that I had been right to avoid it.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Avoid that kind of smothering structure. And I realized how people could endure, because the girls who did accept it and did take it for granted and didn’t have any interior life that they could resort to could be killed by it. I saw people getting killed. That was the first time I saw people getting killed. I’d seen them being made almost unspeakably unhappy when I was a child.

MS. BAYLY: And this is “killed” in the sense of their spirit is killed?

MS. TRUITT: Stultified. Mm-hmm. So limited by rule. And of course it’s very common. I just grew up without it, so it seems to me -- I think it’s tragic. That’s actually what I do think. It is one of the things that sent me toward psychology, the idea of freeing people from the internalization of a structure that bears no relation to the spirit.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

Well, back to Latin. How long did you study Latin?

MS. TRUITT: Five-and-a-half years.

MS. BAYLY: Five-and-a-half years?

MS. TRUITT: Into college.

MS. BAYLY: And so I guess it was all the things that you were taken with, the Latin and the landscapes in Easton and things like that, just sort of built up as you moved into starting your work.

MS. TRUITT: Well, only in retrospect. This is all in retrospect. I mean, I’m telling you as it was as I was living it.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But in retrospect, if I have to put my mind on the structure of how my work evolved, I think Latin had made a huge contribution to it.

MS. BAYLY: That’s fascinating.

MS. TRUITT: And also the structure in my house. I grew up in a very formal, structured environment which was also beautiful. It had the beauty of ritual, the beauty of repetitiveness and the beauty of the beautiful things in the house. And then my mother and father’s behavior, which was very good. Nobody ever raised their voices or anything. Nothing jumped at you. Some of the places that I began to go out into when I grew up a little more, the parents were squabbling and yelling and jumping on the children. The children are frightened.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I was frightened, all right, but I was frightened by their illness. They couldn’t help that. I got a combination of structure and freedom. And I got the strength.

MS. BAYLY: Which is a nice balance.

MS. TRUITT: Hmm?

MS. BAYLY: Which is a wonderful balance.

MS. TRUITT: It’s a very good balance. I’m very interested in balance. And people talk about my sculptures. They’re not -- it’s not a matter of checks and balances, the old cubist checks and balances.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: The balance is interior and runs on the line of gravity that holds the sculptures to the ground. But that concept of balance is something I began to get after when I was very young. I had to balance. In order to keep my freedom I had to balance. It was very interesting, really.

MS. BAYLY: So then in Asheville you were just --

MS. TRUITT: Well, Asheville was really pretty miserable. I had friends because I really like people and, you know, I’m sort of adjustable. But I didn’t understand them. They were interested in boys. Have you lived in the South?

MS. BAYLY: I’ve lived in Washington my entire life.

MS. TRUITT: Well, the South was a revelation to me. They were interested in boys, whom I didn’t really -- in the first place I was too young. I was 15 when I graduated from high school. I was just barely 16 because, you see, when they put me in school, there wasn’t any way for them to tell, when I came out of Ms. Francis’ hands --

MS. BAYLY: Where you fit.

MS. TRUITT: Exactly. So they just guessed, really, I suppose. So I ended up, then, I had to stay home for one year before I went to college. My parents said I was too young, and they were right. But I learned a lot in Asheville. I learned about bulk and weight and, to some extent, about shape. And I learned about structure and I learned to endure.

MS. BAYLY: And did you learn about that from, would you say, the mountains and the hills and the landscape?

MS. TRUITT: The mountains. By that time I was driving. I got my license when I was 14. So not only was I riding on my bicycle, I was driving.

MS. BAYLY: So now even more freedom to explore the terrain.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah, and responsibility, which is, of course, extremely strengthening. Responsibility is very strengthening, and I began to have it when I was about 13, when my parents got sick.

MS. BAYLY: Sort of taking care of the family and your sisters.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah.

MS. BAYLY: From there you went -- from Asheville --

MS. TRUITT: Is this -- excuse me for interrupting you. Is this too much detail?

MS. BAYLY: No, not at all. The detail is wonderful, absolutely wonderful. And please give as much detail as you can.

MS. TRUITT: All right, I will. Then I’ll keep on doing sort of – it doesn’t have to be too much of a linear progression. You’ll keep us to what you want.

MS. BAYLY: Not at all.

MS. TRUITT: Okay.

MS. BAYLY: No, you please just tell me what you’re thinking. I don’t want to interrupt anything.

MS. TRUITT: Well, then I’d like to say a little bit about ancient French poetry because when I didn’t go to -- when I couldn’t go to college -- and my parents were right about that. I was too young. I would have gone then at 16. One of the girls in my class was 16 when she went, and she had a terrible breakdown. Bryn Mawr is a very -- in those days and I think still is -- a very difficult, demanding, scholarly atmosphere.

But during that year, I went to the junior college that was run by St. Genevieve of the Pines, and I had the good luck to run into Mere Jena, who taught medieval French poetry. That was extremely lucky. Then I picked up romanticism, which I had not picked up from English poetry, even though my mother read it to me all the time. I don’t know quite what it was, but it was the French who taught it to me. Anyway, I picked it up, and I picked up nuance. I picked up inflection. You know, that very early French poetry is very beautiful. I picked up inflection, which I really hadn’t picked up from English poetry. So that had a huge effect on me, and I’m very glad I did that.

I also began to write poetry, really bad poetry. I began to write. I wrote during that year. It gave me a sort of a breathing space for me to mature.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I needed it. I needed it. I’d had a lot of stress and strain before I got to Asheville, and then I’d had to adjust to a lot of different things. And I had a year of lying fallow.

MS. BAYLY: You read poetry, and writing yourself.

[Begin Tape 1, Side B]

MS. TRUITT: And reading. I read all the time. And my mother and I talked. The twins were there. My father was there. It wasn’t altogether happy. It wasn’t happy, but it was reasonable. And I lay fallow.

MS. BAYLY: So you weren’t drawn to go on to pursue writing or poetry necessarily from that?

MS. TRUITT: When you ask the question, I think what it implies is that I thought, “Oh, I’ll be a writer,” or something like that. It never crossed my mind to be anything except a psychologist. That was the only thing I set out to be where I made up my mind -- that I had made up my mind toward a goal.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And I didn’t make up my mind to that until after I did exercises at a mental hospital in Asheville, after I’d been for two months at Bryn Mawr and had the bad operation for appendicitis.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: It sounds as if I’m not very introspective. I think perhaps I don’t question my own motives or anything. It didn’t seem to me I needed to worry about it. I was busy breathing and living and --

MS. BAYLY: And doing.

MS. TRUITT: And living my life.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And my mind was in no way assaulted by images, because, of course, there were no images. I guess we had a radio someplace in the house, but I don’t really remember that we did. But I guess it must have been there someplace. And I read all the time and I took walks. I liked the dog and I took walks. And I just existed.

Asheville is a good place to just exist in. The air is fresh, the mountains are there, the colors are beautiful. And when I hit the French poetry and picked up nuance, I began to see things I hadn’t seen before: the shadows and the movement of -- the movement of the clouds over the mountains.

On the eastern shore of Maryland, the sky seems to be uniform, more or less. It’s not a place of clouds. It’s a place where the molecular -- the osmotic -- everything, all the color is held up in osmosis in the moisture, but it’s not cloudy. But Asheville was different. The sky was bright and blue and the clouds were very big -- you know, cumulus clouds -- and there tended to be a lot of wind, so you could watch the shadows on the mountains. So you had two contexts, one on top of the other, looking back on it.

MS. BAYLY: What were the colors like?

MS. TRUITT: And I was very interested in nuance then.

MS. BAYLY: How would you describe the nuance of the colors, or even just the colors, in Asheville?

MS. TRUITT: Just great big blocks of color. You know, I’m blind as a bat if I take my glasses off. My eyes have gotten better since I’ve gotten older.

MS. BAYLY: Really?

MS. TRUITT: I can see you quite well. But I like to take my glasses off, and so I’d just see big blocks of color. And then I’d watch the clouds go over the mountains. And then I used to practice. When I went to Bryn Mawr, I went down the mountain on the little railroad that Thomas Wolfe describes in Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River. There’s a little train -- there was; I don’t know what there is now. There was a single line that went from Old Fort up to Asheville, and it wound through the mountains like this, so. There was a fountain at some point, an artesian well at some point going up the mountains, and you could see it about six times as you wound around it, you see, going up. And you went way -- you went straight up and straight down through these quite big mountains.

And when I was going to Bryn Mawr, I just adored being independent. I loved being alone and traveling. I’ve flown the Pacific eight times. I like to do it alone. So I used to practice being in the mountains. I would -- let me think, now, if I can express it. I would look at the side that I was looking at, and then I would imagine what the other side would be if this side looked like that. In other words, if it went in, I thought of it as going out on the other side; and then if it went this way, toward me – convexly -- then I thought there must be something concave, possibly, on the other side, or the convex energy would flow into a concavity someplace.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But what I did was to project myself into the mountain, so where it went out, I went out; and when it went in, I went in. Sort of like breathing.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And that had a huge effect on me. That was a habit and I got it when I first went to Bryn Mawr when I was a freshman, and I kept it all through my four years. So it made those trips up and down the mountain just heaven for me.

You went up the mountain, you got to Old Fort at 8:00, and they transferred two little cars to a little choo-choo that huffed up the mountain. So you saw the sun come up from the east. You were going due west, but the sun came up from the east and all the shadows went this way. Then you left Asheville, Biltmore, at 4:30, so as you went down the mountain -- depending, again, on the time of year -- the shadows you can imagine.

MS. BAYLY: Right. Of course.

MS. TRUITT: The sun was coming from the west, so the shadows were the other way.

MS. BAYLY: That sounds amazing.

MS. TRUITT: It was amazing. Thomas Wolfe talks about it. He thinks of it more as an umbilical cord, because Asheville was his home place. He was born there. I was not.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I never thought of it as an umbilical cord, but I see it as an umbilical cord. Well, you know, wound like that, and with two ends.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And nourishing. [Laughs.] It’s hard to convey the simplicity of life, without any of the stimuli that everybody is so used to now. I suppose if I were doing it now, I’m sure I’d have a cell phone and I would be in touch with people. And I’m sure now they have cell phones if you even travel on the Metro Line, unfortunately. And my mind would have been filled with secondhand images. But my mind, until I was -- we got our first television set when I was pregnant with Alexandra. That would be 1955. There were no secondhand images.

MS. BAYLY: So everything until that time you could just -- is what you saw.

MS. TRUITT: It was your naked nervous system and mind and spirit, or whatever you want to call it. Your élan, as the French would say, in touch with whatever was right in front of it. You know, the central nervous system only meets the outside world through the eyes. The central nervous system consists of the 12 cranial nerves, of the spinal cord and the 12 cranial nerves, and every single one of those nerves is hidden in the body inside the flesh except for the ocular nerve, which comes right out here in the fovea. So the ocular nerve is in touch with what’s outside of you.

And nowadays -- I’m not objecting to what’s happened, because that would be stupid. It’s a different -- whole different kind of a thing now. But nowadays a great deal of stimulation comes into the central nervous system, and it’s not coming in to the -- less information is coming in through the autonomic nervous system, which is where most of my information came in to me. It came in to my trunk or my body. The autonomic nervous system, the parasympathetic, sympathetic nervous system -- have you studied all this, or --

MS. BAYLY: Very superficially, but yes, a bit.

MS. TRUITT: Well, the parasympathetic and the sympathetic nervous systems function together in a kind of balance to keep the body balanced. They energize it and they also quiet it down. That’s a little thumbnail sketch of it. But most of the information that came in to me came in through that nervous system and my central nervous system through my eyes and, obviously, through the senses. But it was all personal. My children pointed out when they were growing up that my experience is very personal. It’s not selfish. It’s not selfish, but it’s personal. Very personal. And then when I hit the art world, all my relationships there were personal. I had to learn impersonal things, and I’ve never learned it very well. I’m not particularly good at that.

MS. BAYLY: So do you think that’s what kept you, I guess, a bit removed from what one might say is the art scene, or --

MS. TRUITT: You mean when I hit New York? Oh, yes, I think so. I was already rooted in myself. I’m really pretty rooted. But that was a long way from when I was just a young -- very young woman going back and forth to Bryn Mawr.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And at Bryn Mawr I learned, I mean, almost more than I can say. I learned to be independent again. I mean, independence has sort of been the thread that ran through all this. I was extremely lucky. There were 230 undergraduates or something, and there were these great professors. So some of the classes were just two people.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wow.

MS. TRUITT: Can you imagine? You have this full professor and two people.

MS. BAYLY: That’s phenomenal.

MS. TRUITT: Two students. Yeah, phenomenal. And then we had -- it was very strict. In first-year psychology we had eight hours, two four-hour labs a week; and we were expected to write up the experiments as if they were going into scientific journals. The reports used to be 90 pages. I mean, we had to write the materials, the procedures, the course of the experiment, the outcome of the experiment, and then we had to write quite a long essay on the meaning of the whole thing.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So --

MS. BAYLY: It’s quite a bit of work.

MS. TRUITT: Sometimes I wrote those twice a week, and sometimes I wrote them once a week, and sometimes I wrote them every two weeks, depending on the course of the experiments. It was a lot of work. My sisters went to Radcliffe, and their papers were 20 pages or something, which is really nothing.

MS. BAYLY: So that must have taught you a lot of discipline and --

MS. TRUITT: Excuse me?

MS. BAYLY: It must have taught you a lot of self-discipline and --

MS. TRUITT: A great deal. And you had to do everything by hand, you know. I had a typewriter. My father gave me a typewriter, but I wrote everything by hand. I still do. When I’m writing a book, I write it by hand. You see, it’s sort of an old- fashioned life, but then I was born in 1921.

MS. BAYLY: Right. I find writing by hand, you feel like you have more connection to the work --

MS. TRUITT: Exactly.

MS. BAYLY: -- than when you type.

MS. TRUITT: It’s integrated, isn’t it, to your – everything --

MS. BAYLY: Yes. It’s all right from your head and out your arm or --

MS. TRUITT: Or up.

MS. BAYLY: Yes, exactly.

MS. TRUITT: Exactly.

MS. BAYLY: So whichever way it goes, it’s coming out of you, I think.

MS. TRUITT: And it’s honest.

MS. BAYLY: Yes. Yes.

MS. TRUITT: We now have what I call computer books, which are overlong and you can see where the people -- the writers just simply took out -- put in great chunks of information. I found it out from reading a biography of Toulouse-Lautrec about 10 years ago. And I thought, “My god, I can’t wait for him to die.”

MS. BAYLY: [Laughs.]

MS. TRUITT: [Laughs.] One shouldn’t feel that way.

MS. BAYLY: No, not at all.

MS. TRUITT: No. But there’s so much information.

MS. BAYLY: And do you think it’s just from typing on a computer?

MS. TRUITT: It doesn’t cost you anything, does it?

MS. BAYLY: No.

MS. TRUITT: Well, I think I have -- I did diverge. But I think the French poetry was worth diverging for.

MS. BAYLY: Absolutely. Absolutely.

MS. TRUITT: And I think the nuances, the inflections, it was that nun, Mére Jena. I can see her now. She conveyed it to me. So lucky. I was just so lucky.

Where are we now? What would you like me to --

MS. BAYLY: Well, whatever you think. I was going to move on if you wanted to talk a bit more about Bryn Mawr or about your nursing.

MS. TRUITT: Bryn Mawr comes before the nursing. Well, in Bryn Mawr I learned the habits. I already had them from school. I had them really from the beginning, I think, because of just my temperament. You see, because the outside world is just not that interesting to me -- or it is extremely interesting to me, but it’s interesting to me in the sense that I absorb it like a sponge. And I’m very interested in what I do with it and putting it in a kind of an order which will then yield, yield understanding.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So from the beginning I concentrated on homework and making it right, you know, that sort of thing. And I had to work hard because I couldn’t do any math. I didn’t know any arithmetic. Why, you can imagine.

MS. BAYLY: I certainly can.

MS. TRUITT: It was difficult. And I was always counting on my fingers, trying to make it come out. On the other hand, writing for me was just always easy from the very beginning. I think I was just born knowing how to write, as soon as I figured out -- as soon as I was taught – again, in public school. I loved Ms. Francis, but I don’t really think she knew how to teach. But I’m so thankful she didn’t because I was just let alone to kind of grow, again like one of my mother’s cabbages. But Ms. Gretsinger, whom I got in the fifth grade -- I was thinking of her this morning. The people whom you know in your life who disappear because they die and you can’t any longer say thank you, those people sort of haunt you.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, I’m sure.

MS. TRUITT: So Ms. Gretsinger said that there were -- we did something – I don’t know whether people still do it. We diagramed sentences.

MS. BAYLY: Yes, people still do it.

MS. TRUITT: Charlie Finch knows how to do it, my grandson. We diagramed the sentences, and it fitted in with Latin. You have the noun and the adjective and the adverb, et cetera, et cetera. And then she said, “Write three sentences” -- or something like that -- “Write three sentences” -- or one sentence -- “using adjectives and adverbs and nouns.” And I – immediately this picture of green, green water springing out of a mountain and down the mountainside into a pool -- not into a pool, but into a kind of continuation of a river with green meadows on either side, the matching of the emerald water coming down with the emerald grass. So I wrote a cheesy sentence, something about the green water ending up in the emerald grass. I mean, really bad, you know --

MS. BAYLY: Right, right.

MS. TRUITT: -- over-flown writing. Nonetheless I got them all in, and I was interested in that because I could use adverbs, verbs, nouns, prepositions, you know. And from then on I was home free, in a way. I’ve always known how to do it, how to put them together.

MS. BAYLY: That’s wonderful.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah, it was wonderful. It’s as if I recognized how to do it.

Well, back to Bryn Mawr. I learned the habits that have sustained my life, which -- I mean, I confirmed them and they turned out to be very serviceable. And I extrapolated them and strengthened them. That is, the habit of always getting my work done ahead of time, which I almost never broke except once in my junior year when my mother was sick. The habit of making a lot of preparation for something and then doing it in one fell swoop.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So I would read maybe 15 books or something. And we didn’t have “Post-’ms.” I don’t know how we lived without them, but we didn’t. We just tore out pieces of paper and put them in the books and made notes. But in the meanwhile, I formed the structure in my head. I learned to form a structure of knowledge in my head and then distill it out into papers, either into exams or -- we didn’t talk in class much; there was almost no discussion -- into exams and into these long papers.

MS. BAYLY: And do you think this eventually was how you -- you know, when you’re making something, is it the same process?

MS. TRUITT: It’s unconscious.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: At Bryn Mawr it was conscious because it was linear material.

MS. BAYLY: It just sort of stayed with you, I guess, in your subconscious.

MS. TRUITT: The habit.

MS. BAYLY: Yes, the habit.

MS. TRUITT: The habit of taking in a large amount of information. The habit of taking in apt information and then simply living with it until it distilled. That’s what I got. And I didn’t do what other people did, which is to wait until the last minute and then write it. I’ve never been able to do that. If I have an exhibition, if I say I’m going to, I’ve already got the work.

MS. BAYLY: Okay. So everything ahead of time?

MS. TRUITT: Well, everything so there’s no scurrying, you know.

MS. BAYLY: Scurrying.

MS. TRUITT: So that everything is allowed to be itself. And my habits of going to bed early. The other people, very often people would stay up late. The habit of solitude. The habit of going my own way and paying very little attention to other people. Almost none. All my habits, my way of thought.

And then I thought the professors were extremely interesting. They knew so much and it was so available. All you had to do is to ask questions, so I asked questions. And when I asked questions, I got answers; and if I didn’t get answers, then they told me where I could find them. It was just wonderful. I had a perfectly heavenly four years. Sometimes unhappy. My mother died in my junior year, and my senior year was very unhappy. My father was sick, my two sisters were sick in Boston, and I failed my honors because I spent my whole year on the train.

MS. BAYLY: Going to visit your father and your sisters and back to school?

MS. TRUITT: Yes. They were all so sick. Everybody was so uncomfortable. And I told my mother I’d look after them, so I did. On her deathbed she said, “Will you look after them?” I said, “Yes, Mother.” So I did.

MS. BAYLY: Again, obedient.

MS. TRUITT: Hmm?

MS. BAYLY: An obedient --

MS. TRUITT: Also responsibility.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: She couldn’t help dying. She died when she was 54, just barely 54. Terribly young, you know. Very, very young. You know so little in your fifties. Your fifties, you know a fair amount, but you haven’t begun to turn it over in your mind so that it’s -- you’re still in midstream.

I think if I hadn’t gone to Bryn Mawr and if I hadn’t concentrated, I would not have been able to sustain my life. I just don’t. And the other people I know who went to Bryn Mawr, sometimes they didn’t work as hard as I did. And I’m not that bright. I mean, I’m not one of those people for whom everything is easy, and I didn’t have very good training. The nuns taught me French. That was invaluable. And I kept on with Latin, and the nuns taught me a certain amount of structure. But it wasn’t a very good school. I didn’t even know what a footnote was when I hit Bryn Mawr.

MS. BAYLY: So you didn’t feel terribly prepared, then, for --

MS. TRUITT: Excuse me?

MS. BAYLY: You didn’t feel terribly prepared when you arrived at Bryn Mawr, then.

MS. TRUITT: It wasn’t a feeling, it was a fact. I wasn’t prepared. I wasn’t prepared. I had not been prepared by the school. I was just lucky to get in, wasn’t I?

Were there any more questions about Bryn Mawr, or do you want to move on to the Red Cross nursing?

MS. BAYLY: Well, no, unless you have something else you wanted to say. I would like to talk about the Red Cross nursing because I know that that was a very important time for you. And also there is the one event, I wanted to get to too about when you realized that you didn’t want to do psychology.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. It was the second big decision I made in my life. The first one was to go out on my own.

Well, I graduated from Bryn Mawr, and I remember walking up the aisle. I did not get honors in psychology, which I would have done if I’d gotten -- distinction in psychology. I did not get that, and that broke my heart. Well. Well, it did break my heart, actually. I’d worked hard; I should have gotten it. And I would have gotten it had I not become slightly arrogant because it was my fifth year. See, I had two months at Bryn Mawr my freshman year, and my class had gone on ahead of me. I didn’t have that rub of peers that you have when you stay in the same class.

MS. BAYLY: Right, right.

MS. TRUITT: Sort of implicit competition.

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: And that’s not good for the ego. It’s sort of ego inflating. It’s not good to stay on one more year beyond your class. And then my father was sick and my sisters were sick, so I spent a great deal of time with them.

But I learned how to fail. I failed. It was the first failure in my life, and it was a failure on all the levels, on every level. I couldn’t make my father well. I never could make him well. I couldn’t make my sisters well.

When I hit the exams, I was appalled. I realized “Uh-oh,” because in order to graduate from Bryn Mawr you take four four-hour exams in your major subject. And I had not gone back and reviewed Mental Tests and Measurements, which bored me in the beginning. I hadn’t gone back and reviewed Animal Psychology. I hadn’t reviewed Abnormal Psychology, though I got a very good grade on that because I’m interested in that. Et cetera. I hadn’t done enough reviewing, partly from being distracted and partly because I thought that I knew it. And I did. I knew as much of it as I found useful for my own life, which is my way of being. Ever since, I’ve followed that too, and it’s not necessarily intelligent. I just simply have a kind of magnetic center that attracts to itself what I need, but I don’t pay attention to a lot of stuff; I sieve it out.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So I graduated from Bryn Mawr. I was very, very tired. For the first time in my life, I realized what it was to be tired, and I came home and I vegetated for three months at my father’s house in Asheville. And I took the Red Cross nurse’s aide course because my mother had been a Red Cross nurse in the First World War and because I have a very strong impulse toward that kind of helping people. But what I did not know was I was going to be trained how to use my body. I had never used it. I was used to using my mind.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. But the mind stuff that you learn when you’re studying nursing is really nothing; I mean, if you’re a Red Cross nurse’s aide. If you’re a trained nurse you have to learn chemistry and stuff.

MS. BAYLY: Right, certainly.

MS. TRUITT: I mean, it was absolutely nothing for my brain. But my hands and my body – [laughs] -- you have to lift. You have to learn -- that’s where I first began to lift. I use it in the studio today. When I move my sculptures, I’m using the principles I learned then.

MS. BAYLY: Wow, that’s amazing.

MS. TRUITT: Because I move these great big things. I know how to lift. [Laughs.]

MS. BAYLY: It was great training for you.

MS. TRUITT: Great training. I know how to turn a patient over in bed, how to -- you know, how to do the thing. And I’d never put my hands on other people. I knew nothing about that. And the training that I learned from Aunt Nancy to begin with in how to do chores on the farm -- she lived on top of a mountain in Virginia, and there were seven cousins and we all did chores. She taught me how to sew, how to make things there a little bit. But other than that, I never really used my hands. And I’d never used my heart objectively.

MS. BAYLY: Okay.

MS. TRUITT: Objectively. So on total strangers, you know, if you’re a nurse, it’s an extraordinary situation really. It’s intimate. If you’re a nurse, you walk into a room and there’s a patient. The patient is a full-grown, usually, human being, and they’re frightened. They’re scared and they’re anxious and they hurt, and you have to make the bed for them and give them a bath. It’s very intimate. The whole thing is -- you put your hands on their bodies.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: It’s quite an extraordinary thing to do. Fortunately, a very good trained nurse trained us. She didn’t talk about that, but she trained us so carefully and so specifically that we were given exact, detailed instruction about how to go about everything. So we came in equipped. But the psychological part of it is very different from person to person. And, of course, it was in the mountains, so many of the people I nursed were mountain folk. And one of my little chores -- because they give the nurse’s aides what’s called scutwork in hospitals -- was to make little boxes into which the patients could spit, because many of them chewed snuff.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, my.

MS. TRUITT: Interesting, isn’t it?

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: Seems so antediluvian. They had snuff, and they put it in their mouths, tucked it into their chins -- I mean cheeks, I guess, and then they spat. So every morning the old containers of spit -- I mean, I hope I’m not revolting you.

MS. BAYLY: No, no.

MS. TRUITT: No, I hope not, because nothing human – remember Terence, nihil humani a me alienum puto?

MS. BAYLY: Yes.

MS. TRUITT: -- [one of my chores] was to change the little boxes of spit and make nice new ones. So I could talk to the people, too, while I did it.

MS. BAYLY: I think if we could just pause here for one moment?

MS. TRUITT: Excuse me?

MS. BAYLY: If we could pause here for a moment.

[End of Tape 1]

TAPE 2

MS. TRUITT: I think the scientific training, too -- it occurred to me in our little hiatus, I think the scientific training in psychology had a huge effect on me. The paying attention to every single detail without dwelling on it unduly but noting it, being alert to little changes, being alert to facts, I think that had a big effect on me because, of course, I had to write those reports and the reports were based on fact, on observation. The habit of observation and then the habit of deducting from observation. The habit of inducting a fairly large amount of rather complicated information and then deducting from it.

And then the other thing I should mention which really was, I think, pretty critical was while I was there, there was a man named Bordemeyer, Dr. Bordemeyer. He wasn’t a doctor then, he was Mr. Bordemeyer. He was an assistant. He was getting his Ph.D. on the matter of differentiating lightness and brightness in white light.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wow.

MS. TRUITT: Yes. Funny. Right in line with my work.

MS. BAYLY: Absolutely, yeah.

MS. TRUITT: I don’t know which was the cart and which was the horse, but it certainly was the horse because I spent about two years being a subject for him. And he paid me. He paid me $2 an hour or something. He said, “I’m going to pay you.” I said, “I’ll be happy to do it.” He said, “No, I’m going to pay you.” And he was right about that. That was one of my first lessons in how you should always pay. You know, it should be even-steven.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And I sat in a small dark room and in front of me were two circles, and then I was asked to say which was brighter or which was lighter. It sounds mad. It was extremely interesting. The circles were quite big -- about, I would say, 18 inches in diameter -- and they were about maybe 10 feet away from me. And I sat in the chair, and every now and then I just had to have a break. [Laughs.]

MS. BAYLY: I can imagine.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. So he would start me out and he would make the two squares light. They would both be of the same light. Then I would equate those. And then he would give me two squares -- I mean two circles that had the same brightness, and thus he established a kind of baseline. Then he would say, “Is the left-hand circle -- or the right – Is the right brighter or lighter than the left?”

MS. BAYLY: So it must have been very difficult to --

MS. TRUITT: Well, it focused my eyes in a way that only Japan did when I got to Japan, because Japan, the whole landscape, everything in Japan depends on value. I didn’t realize it. What I was judging was value.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wow.

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. From an art point of view.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But it never crossed my mind. I don’t think it crossed Mr. Bordemeyer’s mind. I’m not sure what was crossing his mind. But I used to sit for hours. I think the sessions were two hours or maybe until there’s some optimal place and then you can’t do it anymore. And every now and then I would go off and he would correct me and pull me back to what I had judged before. And that was his Ph.D. thesis. And I read his obituary in the Times about five years ago.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, my. Did you ever read his thesis?

MS. TRUITT: No. He went to the University of Michigan. He left Bryn Mawr and he went to the University of Michigan, and there he got his Ph.D. I think they called him to be an assistant professor. He may have been getting his Ph.D. from University of Philadelphia – Pennsylvania. Bryn Mawr had no male students then.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: I’m glad I remembered that because those two things factored in.

MS. BAYLY: I see.

MS. TRUITT: A great deal factors into an artist’s life, as you’ve undoubtedly discovered.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: Everything factors in. But we should try, I think, to just touch on the little things that were particular, particularly important.

MS. BAYLY: Would you want to talk about -- back to the nursing?

MS. TRUITT: Back to the nursing. Well, I learned never to flinch, because you do bedpans, lots of bedpans. You do very intimate things for people. And not only would I never flinch anyway, because I think to flinch away from anything anybody does or any product they make or to flinch from anything is a kind of lie. And so I learned not to. I learned to accept pus and feces and urine and to always be cheerful and never to show what I felt. And if I -- it’s hard to see people suffer. And how to be comforting in ways that would not have occurred to me before because they depended on hands, not on words. Words are no good to patients.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: And it also cultivated in me a kind of physical empathy that I do not think I would have had otherwise. The kind of empathy I had with the mountains, but that was my imagination.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: These were living human beings, and on my empathy with them their comfort depended. So if a big strong man has a broken right arm, not only does he feel frightened for the future, but he’s never had pain before, usually, you know, if they’re strong and young. And you have to be careful never to -- I mean that whole area of the body is sort of sacrosanct. You have to be careful about it. And yet you have to handle it in a very matter-of-fact way. Everything has to be handled in a matter-of-fact way. So you say, “Oh, I see you’ve had an accident. Oh, well, we’ll fix it up.” So then I would fix it up.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So that influenced the way I brought up my children, too.

MS. BAYLY: You were just sort of --

MS. TRUITT: Yeah. When something happened and they spilled or god knows what, I would say, “Oh. Well, we’ll fix it.” My attitude toward things was we’ll fix it.

MS. BAYLY: Right. Take care of the problem.

MS. TRUITT: Take care of the problem and not make much of it, and never -- always to defuse.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: So that’s it. I got that training.

Then what happened is, during that summer I got rested. And before I left Bryn Mawr, I had gone up to -- I decided -- I’d always wanted -- I intended to get a Ph.D. and to be a psychologist and to do what I could to alleviate suffering, I thought, on that level. So before I left Bryn Mawr, I went to Yale and I went to see Dr. Clarke, who was the head of the department, whose experiments I had read about so I knew about him. I called him up and I made an appointment and I went up to New Haven -- where my grandson’s about to graduate in about two weeks.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, wonderful.

MS. TRUITT: Life is so interesting because it turns, as you know -- you must already have noticed -- it turns on itself.

MS. BAYLY: Exactly.

MS. TRUITT: So I went to see Dr. Clarke, and we sat in his office and he urged me to come to Yale. He urged me to come and stay, and he said, “Come and stay with us.” I was in that old Taft Hotel. My, it was uncomfortable. And I said, “No, thank you,” because even then I knew that you must never -- you know, I didn’t want to get too close to him, because he was going to teach me. So I went through the application, which I finished when I was down in Asheville after I graduated, and sent it in to Dr. Clarke. And in late August or early September, sometime around in there, I got a letter back saying, “Dear Miss Dean: We’re glad to offer you a place as a graduate student at Yale.”

And when I read it I thought, “Uh-oh.” You know that funny little feeling you have that the thing is really, after all, not exactly right?

MS. BAYLY: Exactly.

MS. TRUITT: So I went for a walk. I’ve described it in my book, so I won’t dwell on it. But I went for a walk and I made up my mind that I wouldn’t go. I realized I could. My brain by the time I graduated from Bryn Mawr was so honed, you know, you could give it anything. It was like a performing dog.

MS. BAYLY: [Laughs.]

MS. TRUITT: [Laughs.] You could give it information and it --

MS. BAYLY: It would know what to do with it.

MS. TRUITT: It would collate it and put it in order, and then it would be able to make something new out of it. And it just was a perfectly good functioning mind. And I wrote Dr. Clarke and he was very disappointed, actually. I think he really wanted me to come. It was during the war. If you were alive and breathing, you know. I think that’s one of the reasons they accepted me, because the acceptance letter said, “You might be interested to know we’ve never taken a graduate student at Yale with such a low grade in math.” Because I’ve never really understood it, you know.

MS. BAYLY: Right. Right.

MS. TRUITT: So I wrote and said no. But before I did that, I made up my mind what I would do -- since it wasn’t a negative decision. It wasn’t against Yale, it was for what I had learned outside of academia. So I decided I’d go to Boston and get a job, and that’s exactly what I did.

I forgot to say that when my mother died I inherited money. Without the money that I inherited, which is not masses and masses and masses, but a respectable amount, I wouldn’t have been able to live either because I’ve invested in myself all my life, and my --- education for my children and grandchildren. So I was independent.

MS. BAYLY: This affords you the opportunity to make many more choices, allows you --

MS. TRUITT: Yes.

MS. BAYLY: -- to choose what you would like to do.

MS. TRUITT: It allowed me to choose. It gave me freedom. I’m grateful to my ancestors.

MS. BAYLY: Oh, certainly.

MS. TRUITT: Don’t you think?

MS. BAYLY: Absolutely.

MS. TRUITT: Yes. Really grateful. Grateful to all the circumstances in my life, really. Although one has to watch out for post hoc, propter hoc reasoning; you know, that because something comes after something, that the previous factor was the cause of it.

MS. BAYLY: Right.

MS. TRUITT: But in any case, I am grateful. So then I just took a train and went to Boston. It seems amazing, doesn’t it, in a way?

MS. BAYLY: Very much.

MS. TRUITT: I mean, I was 22. I was healthy. A 22-year-old in the middle of the war. And I got a job out of the Massachusetts General Hospital -- I’ll launch us into this -- for the National Research Council for $150 a month -- which was a good salary in those days -- for the Williamstown project, which was a group of 10 people, young people my age, who were at Williamstown, Massachusetts, at Williams College, where a whole squadron of naval air cadets -- people who had been accepted into the Navy who were air cadets -- were being trained to fly. They hadn’t started their flight training yet. They were doing their preliminary studies at Williams College.

So up I went. Two doctors drove me up there and I stayed at a boarding house with the other people who were working on the project, who are still my friends, those who are alive. Who is alive out of that group? One.

MS. BAYLY: Really?